(Originally printed in the September issue of Expat Parent, http://www.expat-parent.com)

By Carolynne Dear

There’s a gentle buzz of conversation and the chink of cutlery scraping china as I am whisked through an elegant Edwardian dining room and into the even more glorious confines of the “Blue Room”. It is lunch time at the Helena May, as members and their guests enjoy a cool catch-up over a meal or a drink, on what is a stinking hot day outside.

This is Hong Kong’s “club for women”, a private institution for Hong Kong’s ladies to meet, socialise and network, and I am here to find out more about its remarkable past from current chair of council, Tina Seib.

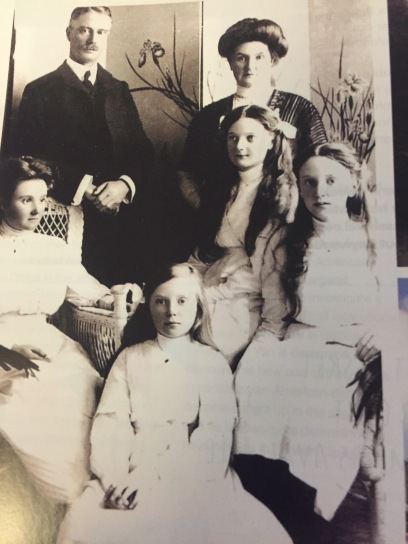

It was set-up and initially run by Lady Helena May – wife of Hong Kong’s then governor, Sir Francis Henry May – and financed by various wealthy donors of the day, including Ho Kom Tong, the Ho Tung family and Dr Ellis Kadoorie.

Its raison d’etre was as a safe and comfortable refuge for the increasing numbers of single, expatriate women arriving in Hong Kong. As a mother of four daughters, Lady May was no doubt well aware of the lack of facilities in Hong Kong for single women at that time.

The beginning of the twentieth century was a period of increasing independence and social mobility for women. The suffragette movement was in full swing in Britain, while new technology – such as the telephone and the typewriter – was opening up jobs suited to “female characteristics”, namely “nimble fingers” and a “polite manner”.

Many women ventured overseas – in search of employment and adventure – encouraged by advertising from the British Women’s Emigration Association, as well as male migration.

“Of course a certain percentage came on a husband-hunting mission, as was common at the time,” explains current chair of council, Tina Seib. “But many others came to work. Whatever their reasons, these women needed a safe place to stay, a respectable address for job applications, and somewhere they could meet other women.” Modern Hong Kong is a world away from the city of the 1900s where disease and neighbourhoods of ill-repute were widespread.

Over the years, the club has become somewhat synonymous with its matronly 10pm curfew and “no gentlemen upstairs” rule. But this should not detract from the role it played in enabling many single women to live and work comfortably in Hong Kong in what was then a strongly patriarchal society.

The club still boasts accommodation, both for long and short-term stays. “The residents effectively live in a grand mansion house and have the run of the place,” enthuses Esther Morris in her book “Helena May”. “There is nowhere else quite like it.”

One such resident was Joan Campbell, current principal of the Carol Bateman dance school housed within the Helena May building. She arrived in Hong Kong in the 1950s as a young dancer and initially stayed in the Blue Room at the Helena May, the residential area of the club being full at the time. This year, she found herself on the Queen’s 90th birthday honours list and received an MBE for her contribution to dance in Hong Kong.

“We are lucky to have an immense pool of talent and skill-sets amongst our membership today,” says Seib. “Whether they are homemakers, mothers, lawyers, journalists, bankers or architects, Hong Kong born-and-bred or here on a fleeting two-year contract, our members all have something positive to contribute to the club. The varied membership also continues the club’s tradition of being an excellent networking base for women.”

Indeed all members are expected to volunteer towards the running of the Helena May in some shape or form, whether it’s manning desk in the library from time to time, advising on building maintenance, or helping to organise charity and social events.

The grand Edwardian building itself is an adaptation of the Renaissance style, designed by architects Denison, Ram & Gibbs, who also worked on the Matilda Hospital and the Repulse Bay Hotel. It originally boasted a recreation ground, a lecture and concert hall, a reading and writing room, bedrooms on the first floor, and a room “for afternoon teas, where members are allowed to bring in their gentlemen friends.”

Seib is keen to impress that the maintenance of the building, the outside of which is listed, is the responsibility of the club’s council. The last three years have seen extensive renovations, including re-wiring, damp-proofing and the opening up and restoration of original ceilings covered over during the 1980s, most notably in the elegant Blue Room.

The Helena May was deliberately positioned close to Central, close to the Peak tram (the Peak was home for most colonial ladies who would have been involved with the club), close to the Governor’s house on Upper Albert Road, and just across the road from St John’s Cathedral. In those days, Garden Road was just that, a leafy enclave. These days the club battles somewhat with the noise from the concrete overpasses that now thread their way through mid-levels.

To non-members, the club is probably best-known for its extensive library, and for its ballet school – The Carol Bateman School of Dancing – which has seen thousands of tutu-bedecked children trip through its doors since it was founded in 1948. Bateman had been interred in Stanley during the war and was anxious to start children’s dancing classes as she had done in Shanghai before the war – she began with four sessions a week, renting a room for 20 pounds.

The library was founded in the 1920s and today holds the largest private collection of English-language books in Hong Kong.

During the second world war, all the books were removed and replaced with Japanese tomes in a propaganda drive to impress Japanese culture onto an unreceptive local Chinese population. The club itself was used for stabling horses and was completely looted by the Japanese.

After the war, members were encouraged to “bring a book” each time they visited the club in an effort to return the library to its former glory. The children’s section now contains over 6,000 books and junior club membership is offered for free so children can use the library (“book borrowing by children is surprisingly on the increase,” notes Seib).

The Helena May is also still very much a charity-driven institution. It supports a different charity each year – this year the Marycove Centre in Aberdeen. There is a student mentoring programme in conjunction with Hong Kong University, and the club also offers two scholarships each year for the Hong Kong Academy of Performing Arts. A former recipient of a Helena May scholarship, Pik-sun Chan, now a professional musician, returned to perform at the club’s centenary launch celebrations in February.

In a rather nice twist, the club shares its centenary with the Hong Kong Girl Guide Association, a group with which it still retains links. Each year, English-speaking members volunteer to test local Guides working towards their English Conversation Badge at an Annual Assessment Day, where the girls and their families are invited into the club.

Its graceful interiors coveted by many a bride-to-be, the club also hosts around 50 weddings a year.

It may not be the hippest club in town, it has no sporting teams to boast of and its facilities are minimal, but in its own way the Helena May has quietly stayed true to its mission of supporting Hong Kong’s women for one hundred – often tumultuous – years.

As I take my leave, Seib points out a golden plaque that has recently been hung in the front porch. It’s engraved with all the women to have taken the chair of the club since 1916. “We’ve never had anything like this,” she says, giving it a quick polish. “The club has never really boasted about what it has achieved. And then I thought, why not? These women have quietly worked so hard. So we had this little plaque made.”

Indeed, as remarked by the Bishop of Victoria during the opening ceremony: “The management of this Institute… shall not be an easy task. I shall watch your work with an interest.”

It would seem that the ladies have done him proud.